The Last Dance: Is Michael Jordan’s documentary a giddy puff piece?

Shortly after ESPN won its first Academy Award for Ezra Edelman’s nonpareil, an award-winning piece of investigative journalism that was praised by Mailer and Caro as a masterclass in long-form journalism, the network launched another multi-part documentary Renewed TV Shows about an American sports icon. The Last Dance is a 10-part documentary jointly produced by Netflix. It promises a deep dive into one of the most iconic stars and fabled dynasties of sports history: Michael Jordan and his 1990s Chicago Bulls.

The excitement only grew with the release at Christmas of a glossy extended Trailer that featured never-before-seen footage as well as a star-studded list of interviewees. Justin Timberlake! Jordan will also be participating in the show, despite not speaking much about the Bulls’ imposing reign and dumbfounding dissolution over the past two decades. Initially scheduled for release in June, the premiere date was moved to April by ESPN after the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic.

It has been entertaining in every way possible. The narcotic lure of nostalgia and the smooth blend of archival footage and present-day interviews, combined with a free soundtrack, breathes new life into even the most well-known plot points of Jordan’s journey from precocious child to larger-than-life symbol, both mysterious and overexposed. It is one of the few American sports stories that deserves such a large screen. The episodes have been broadcast on Sunday nights for the past month as appointment television. They averaged six million viewers per episode over the six first installments, ahead of their international release on Netflix. Even the opening notes to Sirius by Alan Parsons Project, which were used as the backdrop to Bulls’ player introductions, and are perhaps the closest American analog to the All Blacks’ haka to pregame stagecraft that can produce spine-tingling emotions, still elicit chills.

The Last Dance is a poor example of journalism. ESPN did not mention that Jordan’s production company Jump 23 was involved in the project’s development. This fact is hard to find from the credits, which are and omitted. The Wall Street Journal’s Ken Burns, an American documentary filmmaker, was one of the few who noticed this detail in the film’s enthusiastic reception. He described the arrangement as “the opposite of where we should be going”. Burns stated that if you are presently influencing the film’s making, it could mean that some aspects you don’t want in will not be in. “And that’s no way to do good journalism… it’s not how you do good history. My business.”

ESPN’s failure not to reveal Jordan’s final cut might not have been a problem if it was presented as a point of view piece in the spirit of 2002’s The Kid Stays In the Picture. This leaves it up to the viewer, who must interpret the unreliable narration to find the truth. The Last Dance, however, has been presented as a complete account. It is also subject to the biases and defects inherent in any authorized biography. However, it does not take into consideration those who are cast as villains (even, if they aren’t alive).

The project was unable to get off the ground without concessions. The nearly 500 hours of behind-the-scenes footage from Jordan’s 1998 title season with the Bulls, which forms the narrative spine to The Last Dance, have not been made public due to a pact between the star of The Last Dance and the NBA’s entertainment division. This stipulated that any of the footage could only be used with his consent. Commissioner Adam Silver called back to (who else?) ESPN: “We agree that neither one can use this footage without permission from the other.”

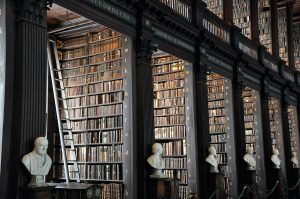

Michael Jordan was the driving force behind the Chicago Bulls dynasty of the 1990s. Photograph: Mike Powell/Getty Images

After many rejections over many years, Jordan finally accepted a proposal in 2016. According to some reports, Jordan gave his approval just days after LeBron’s famous NBA finals win over the Golden State Warriors. This may have been a case of serendipitous timing.

The difficult choice between The Last Dance’s thinly disguised hagiography and no film at any time is easy. The near-psychopathic competitive streak of Jordan, a Daniel Plainview-Esque Daniel Plainview, has been meticulously documented. But, watching a 57-year-old man reflect on this image and weigh in on decades-old scores is undoubtedly compelling theater. However, the Last Dance’s most ambitious promises can only be kept in the subject are allowed to be reviewed and edited.

Although the story is billed as a “warts-and-all chronicle”, it doesn’t completely gloss over Jordan’s legacy that has been the subject of urban legend and whisper networks. However, he addresses them on his terms. Although his compulsive gambling habits and tyrannical tendencies with teammates may seem problematic at first, they are made to look forgivable towards the end. Jordan speaks out for the first time about his “Republicans Buy Sneakers, Too” apoliticism. This trait has not aged well in the post-Kaepernick resurgence. However, the filmmakers didn’t think it worth speaking to Craig Hodges, who was a key contributor to Jordan’s first two championship teams and has been one of his most vocal critics – an odd omission considering the over 100 people within Jordan’s circle that were interviewed. The unshakeable feeling that we are not seeing Jordan the way he wants us to see him is what we get.

This is not an indictment against the filmmakers, but a commentary on our media environment. As much as we would love to see the material in the hands of Pennebaker, Burns, or Asif Kapadia’s hands, that’s not possible in an age when the giants of entertainment and sports can control the narrative through their own production companies, or friendly platforms such as the Players’ Tribune. This trend was pioneered by Jordan, which, it must be noted, was decades ahead. ESPN, which is a rightsholder that broadcasts NBA games annually, is not the only culprit in blurring journalism and entertainment. Look no further than Fox News’ Verheoven-flecked pantomime or Jeff Zucker’s cringe-worthy work at CNN. Here, the promotional videos for presidential debates would feel right at home on Monday Night Raw.

The Last Dance may feel like a missed chance if it was available. While it may not be high-profile journalism ESPN would love for it to be mistaken as you could make a lot worse in the new genre of long-form branded content.